w/ Hsiaowen Hsu 許筱玟

Hsiaowen Hsu is a filmmaker from Taiwan, who graduated in 2024 from Columbia University’s School of the Arts with a concentration in Directing. Prior to her time in New York, she gained extensive experience working on numerous professional film sets in Taiwan, where she honed her skills in on-set production and the nuanced development of character and story.

Questions by: Ariel Xinyu Peng & Hua Hannah Zhong

Hosts: Ariel Xinyu Peng, Hua Hannah Zhong, and Lily Huang-Voronina

Translation & Editing: Ariel Xinyu Peng & Ang Xu

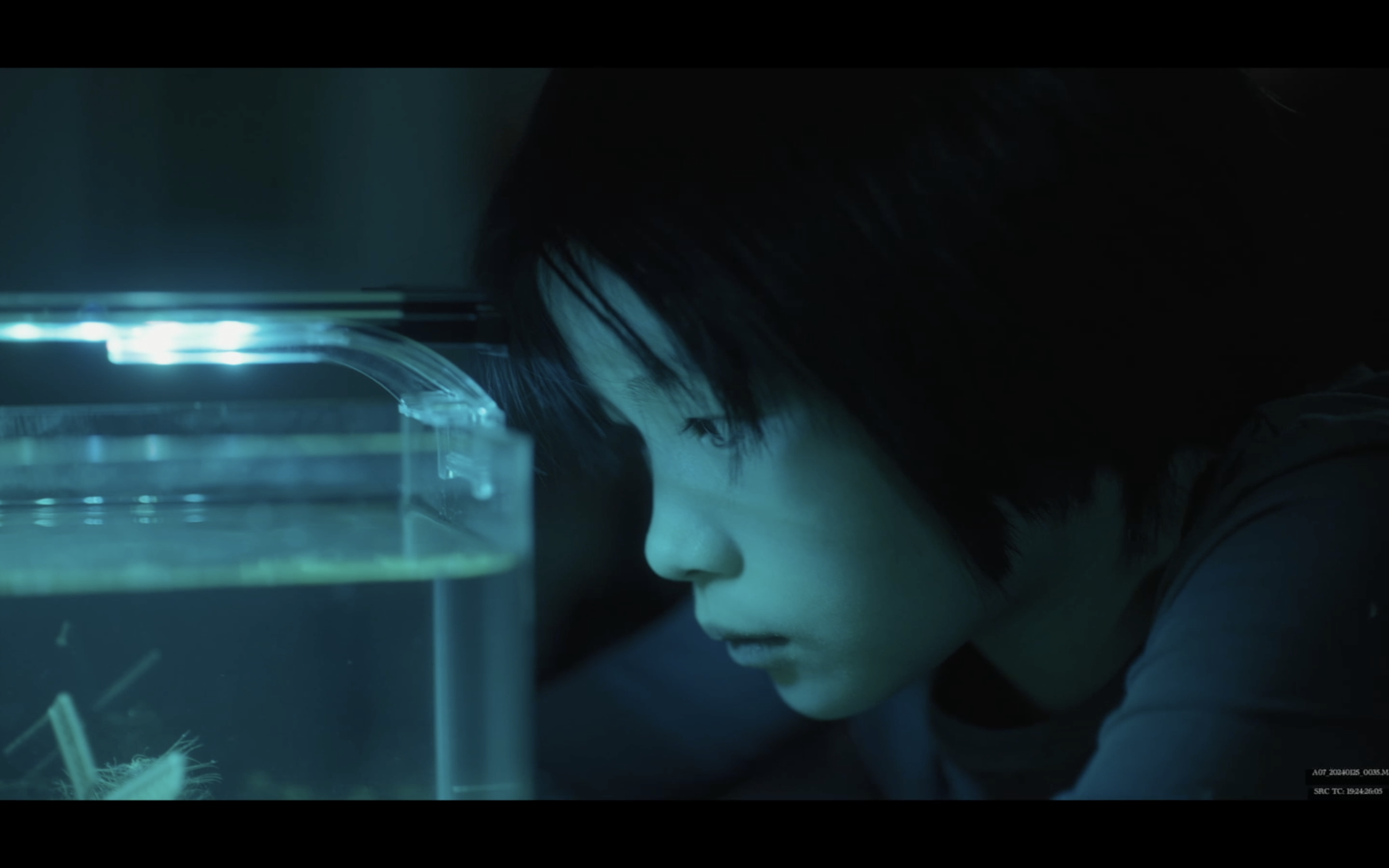

Photo: Hua Hannah Zhong

May 13, 2025

The following article is translated into English from Mandarin, which is the primary language spoken in the podcast.

Hua Hannah Zhong (HZ): How did you get into filmmaking?

Hsiaowen Hsu (HH): I majored in Radio and Television in college and got my hands on filmmaking. I’ve had doubts along the way, but I thought—if I’ve made it this far, it must mean that I like making films.

HZ: How do you start a project—from an image, a feeling, or characters?

HH: A lot of times I start with the personal—something that has left an impact on me, something that I can’t get over with. I don’t tell these stories because I want to be seen but because I want a resolution within myself. Writing about them pushes me to understand them better, such as how people act differently in their respective positions.

Ariel Xinyu Peng (AP): You’ve told us previously that the topics you’re most interested in are family, relationships, and cultural differences—why are you drawn to these topics?

HH: These are the three things that I encounter most in my life.

HZ: You’ve worked in both Taiwan and NYC—how does the cultural dynamic in New York impact you?

HH: When I first came to New York, the biggest difference I observed as someone who grew up in Taiwan was how students in my MFA program collaborate. In Taiwan, everyone was always doing more, taking on unnecessary tasks, which we call social etiquette. Here, I had to get used to simply leaving when you’re done, no need to stay and help others. People here don’t guilt trip as much. Though you can nitpick on the lack of “etiquette,” this mode of operation is simply easier for me.

AP: As a female filmmaker, what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve had to face?

HH: At first I didn’t really think of myself as a FEMALE filmmaker. Making a film was kind of like being in the military, and its completion required hierarchy to some extent. Not everyone is equal on set, though to what extent is a more intricate matter.

However, based on my personal experience——I’m not trying to define anyone or anything: back when I worked on sets in Taiwan in my 20s, some male crew members, especially the cinematographers, would tell sexual jokes, tease me and even harass me, while bossing me around and yelling at me. They treated men in less powerful positions the same way, albeit without the sexual element, but you could do nothing but smile at them.

By and by, I realized that women on set experience harassment far more often. In many Asian cultures, men in positions of power tend to act more forcefully—especially in the tech departments. After I came here, I saw a lot of things that surprised me—like petite women pushing dolly tracks—and I thought it was really great. I love that. Here, I’m allowed to handle heavy machinery. I could never have imagined working as Assistant Camera back in Taiwan, although I think the situation there is improving.

I told myself not to treat others this way: never become those people. And when I’d become older, I’d still treat those who were younger with respect.

AP: Are you influenced by traditional values? Do you try to break free from them or do you still see some good in them?

HH: More often I try to break free. I grew up in quite a traditional family. The overall atmosphere was that we need to obey the man. For instance, we must eat according to Dad’s schedule. When we ate, no one dared to talk until he left. We never knew why we couldn’t talk—it wasn’t like Dad specifically told us not to, but it became the status quo. We whispered when he went to sleep. When we traveled and stayed in the same hotel room, Mom would cover the TV so it wouldn’t be too bright for Dad when he wanted to sleep.

On the other hand, I do think my mom was partially responsible for the status quo—she made us normalize it. I thought that, while these women are victims of traditional values, they hold themselves in that position.

My parents argued a lot, all about tedious stuff, such as when it’s meal time but food’s not ready, he’d get mad. My mom was in a constant state of anxiety and fear, so I used to feel bad for her and even wrote letters to Dad asking him to be less horrible with Mom. But as I grew up, I realized that this was her choice all along, and she could only be comfortable living up to these traditional, outdated values. So if I were to say to my mom, don’t listen to Dad, she would be scared and not know what to do instead. I can only respect the ways of my parents, since that’s what they’re comfortable with, but I don’t like that, so I don’t live with them. In a way, I respect traditions but want to break free.

Therefore, when I meet those people acting all macho and asserting dominance all over the place on set, I often ask myself why I feel so uncomfortable. Knowing how to deal with them makes me hate it even more. I often think, why TF should I make you comfortable! But I didn’t have the guts to say it out loud because I was taught this way, to obey in front of authority figures. From my observations, those macho people, while having huge egos, are in fact very fragile. So if I spoke out, they’d get upset, and hence ruin the vibe. But still I don’t like this about myself. 🙁

Out of Factories

HZ: Can you tell us about your documentary Out of Factories?

HH: Based on a novel written by Yang Qingchu about women who worked in the factories in the era of the “Taiwan Miracle,” there was a historical drama that needed promotion in the form of a documentary, so I took on the job and started with nothing but an idea. I worked really hard on finding these women: I barged into a lot of factories. Eventually, I picked these four aunties out of the fifteen or so I talked to, as they had the most personalities. The first auntie had a bumpy marriage, but her son gave her strength. The second auntie was good at her job but had a hard time getting a promotion. The third auntie had romance and love take up a big part of her life. The fourth auntie’s story was about protests.

At first I romanticized them as storytellers who carry shocking memories of the era. Later I found out they were only living life. They needed money, so they went to work.

AP: I really like what you said about going in with romantic ideas, idealizing these four women. As you made this documentary in a whole new era, they also had to let go of their personas from decades ago. Do you think it was more difficult adapting to new lives for them?

HH: Moving onto the next stage in life must be difficult for everyone. Same case for my parents: during their time, you could make fast money, as long as you had a job. So it probably rings true for everyone in that generation, they were always adapting to the current.

HZ: How did you get these aunties to share such personal experiences?

HH: It felt like how you interact with your subjects were the core in the process of documenting, so I approached them with the friendliest, most personable look possible. I interviewed every auntie two to three times. Our first interview with the first auntie generated great materials, but from the second time on, she started to treat me like a close friend, almost like her own daughter, and many things she said couldn’t be used for the documentary. So when the shooting was over, it felt like I was abandoning her, which made me sad.

The third auntie was reluctant at first, but she was such an interesting character that I almost begged her! One of the best materials happened when her husband suddenly came into the room and started singing while I was interviewing her. This would have been such a good scene for the documentary, but my cinematographer forgot to turn on the sound. 😡 On the way home I was so mad.

AP: That’s so surprising, because after watching the documentary I thought the third auntie was the most lively. Did making this documentary change you in any way?

HH: At first I had too many ideas. I was way too idealistic and romantic. Later I realized the best I could do was record these four aunties and how they impacted me. I stopped taking on the role of an analyzer from a higher perspective.

HZ: Have the aunties watched Out of Factories?

HH: Yes, and they got really shy, though they still finished watching it happily. The first auntie watched with her son, who was also in the film industry. In fact, he was the one who introduced me to his mom, because he wanted her to see what his life looked like, as a filmmaker.

HZ: What are some of the biggest differences between making documentaries and other genres?

HH: Someone has said to me, making documentaries is about searching for the dramatic aspects in real life, and making dramas is about looking for the life-like elements in fiction. When making dramas, it’s often about what you want to talk about. However, when making documentaries, it’s about what others want to talk about. Especially since it was me who created this opportunity.

What’s fun about making documentaries is that something is bound to happen, every day you walk on set. Even though prepared, I can make adjustments as I make the film. I enjoy having a small crew, because I can communicate with my cinematographer and go as things happen. Even though having preparations done beforehand, I can make adjustments as I make the film. I also like having a small crew, since I can communicate with them and go as things happen.

I hope to make a film about the people unseen in this society, such as prostitutes, the people who come with a lot of stereotypes about them. I hope to be able to see them from new perspectives, and I would make a documentary, not a drama. If I’m making a drama, I’d need to conduct a thorough field study before shooting, which can still assert bias, ending the subject up with more stereotypes. For instance, I really wanted to make a drama about kids in orphanages for my thesis. But the more I visited them, the less I knew about them. If I were to continue writing that drama, I would definitely regret it.

A director once said to me, you have to think about making a change when making films about mystified subjects. But I don’t think we have that right—all we might do is present something in various perspectives.

AP: I really appreciate this answer, especially as a nonfiction writer myself. You need to be responsible for your subjects, not just say that you want to represent them, out of nowhere.

HH: Yup, otherwise it’d seem commercial.

The Snitch

HZ: Let’s move on to another film of yours, The Snitch. Can you tell us what it’s about?

HH: It’s based on something that happened to me when I was little. Some kids would cheat during quizzes. While I thought they did it for fun, I felt bad for our teacher. Since I was an extremely empathetic kid, I wanted to tell the teacher the truth. But the nightmare started after that, as everyone started pointing fingers at one another for being the snitch. I got really scared so I went to the teacher’s office and told her, “I actually cheated all the time too. I lied to you”. For some reason she believed me, and told me that she was disappointed in me.

This episode is one of the many instances of my growing up, though it isn’t the good kind of growing up, it is about growing up nonetheless, which it’s not purely about doing the right thing.

AP: Portraying a “coming-of-understanding” story from a kid’s perspective does seem to be a more unadulterated approach.

HH: I viewed things in black and white as a kid, but as I grew up, I found that there is a grey thing in between, and it would always be there.

HZ: What are the differences between working with kid and adult actors?

HH: Kids are so much harder to control, so sometimes we had to “catch” them.

AP: Catch them as in catching them with hands…?

HH: No no no, as in capturing them with cameras! 😂😂😂 Kids are an entirely different species, and they get tired easily. They wouldn’t follow instructions, but would do random things all of a sudden that might be good for the film. Therefore we used a lot of handheld cameras.

My Assistant Director tried helping the kids channel the script to things they would encounter daily. For example, “think about the moment when you sneaked a look at your textbook during a test and channel that feeling to the scene. I know you know how that feels.” Shout out to my AD and my casting director! They guided the kids like teachers.

HZ: What makes a successful director?

HH: I admire the people who keep their own faith and respect others. But being a “good person” is another thing: being nice doesn’t get you success in this industry. You gotta have your own set of rules and build your own boundaries.

AP: What are some good qualities to have on set?

HH: I admire the people who keep their own faith, respect others, and can own up to their mistakes. I once worked with a director who threw tantrums before figuring out a solution, which got everyone else constantly on their nerves. For instance, he would get upset when he thought someone had moved the lights, and no matter how we tried to move them back, he wouldn’t be satisfied. I was also translating for one of the crew members, so he thought it was my fault for not having notified him in advance.

HZ: In short, be a good person before being a good filmmaker.

AP: I’m picking up a lot of miscommunications. To me, respect means using the language that the others can understand when communicating.

On Translation

AP: I know you and Lily are working on the subtitle translation of the Snitch. What are some challenges that you’ve faced in the translation process? For instance, what is the function of your dialogues? And are there things that you find are just completely lost in translation?

LH: I really like this question!

HH: Dialogues are difficult because they are intentional. And sometimes, for example, the kid actor might say something better than what I’d written, so I let them say the lines in ways that they themselves normally speak. Some dialogues were off-script. No matter what, the dialogues MUST be natural, organic, as bad ones tend to trip everything up.

AP: Also the dialogues in the Snitch are highly colloquial. Besides, kids talk differently than adults do. With the nature of subtitles, it'd be different than saying like you're reading a piece of prose.

LH: Absolutely. This translation is very meaningful to me—especially as someone who went to school in both English and Mandarin environments, I was deeply motivated.

At first, I didn’t think I’d need a dictionary at all—the dialogue was colloquial, and Chinese is my mother tongue. But I quickly ran into challenges with phrases like “从后面往前传”, something you’d only understand if you’d actually sat in a classroom in a Chinese-speaking environment. In American classrooms, where individualism is emphasized, this action simply doesn’t exist.

So as a translator, you’re faced with two options. One: be transcendent, not literal. Try to evoke the same feeling for someone who grew up in an English-speaking culture. As storytellers, we know how to do this. But it blurs the line—we start crossing from translator to co-creator. That raises ethical questions: How far over the line are you willing to cross? Where do you and the primary creator align—or diverge—in intention and trust?

The second option is more conservative: go for accuracy, even if it means losing emotional nuance. I often had to find a careful balance between the two.

Another challenge was translating how kids speak. Kids don’t cherish efficiency when speaking, and sometimes they repeat speech for no reason at all. But filmmaking and subtitling are very adult things to do—so how will you justify the two [juxtapositions] at the same time while not straying from the primary creator’s intentions?

On another note, I came to America when I was in middle school, so I had to guess how an 8-year-old American kid would speak. For this, I did something brilliant: I situated the school somewhere in Houston, Texas. (laughs) I made it Southern English! By doing so it allows me to be authentic with the natural, organic feel of the dialogue. If I were to give it a more generic voice in English, I wouldn’t do justice to Hsiaowen’s lines.

AP: Were there anything that you simply must let go of? Would you call those things “lost in translation?” Even though I don’t really like this expression, it does describe a certain sentiment.

LH: Yes, more often than expected. I think my bottom line was not to butcher. If I can’t make a choice between the two options I mentioned earlier, I’d stick to the original text. For instance, the way that family members interact with each other, how power is exerted, from the point of dialogue, differs hugely from that in a North American family. Parts of the story would hardly happen here. In this case, I choose loyalty over creativity. I still have to remind the audience that this is an Asian story: I can’t let that go for the sake of smoother syntax or diction in English.

However, there is still a lot more I can do for better phraseology. For instance, there are places I could add more intensity to, so then the English audience might have a more immersive experience reading the dialogue. Chinese is a very implicit and reserved language, particularly since we are dealing with conversations between kids and adults here.

Funny enough, I haven’t had a chance to talk to Hsiaowen about this translation work—but you got it out of me. :)

AP: Do you feel that you’re understanding Hsiaowen a little better now that you’re translating her work?

LH: I think I’m understanding her better as a creator. We know that the Snitch is partly based on her own life, it sort of feels to me as though this film wasn't written by her but bled out of her…

AP & HZ: This is such a Lilian way of description.

LH: Am I an adjective now?

The Industry & More

AP: Are there plots that you think are getting tired, like we can write about something else for a change?

HH: I’ve thought about this before, but some topics never tire, because in the end, they all speak to different facets of the human experience. So the challenge lies in how to shed new light on something old—family, marriage, midlife crisis, childhood trauma, etc.

AP: What do you think about the biopics and the remakes nowadays?

HH: Those things definitely have their places in the market. For instance, I had a lot of mixed feelings about shooting vertical dramas. Though I was in it because I had to make dough, I thought, I graduated from Columbia and got an MFA! It sure felt like being slapped in the face, but I had to accept that these things sell, and further put myself in a humbler position. Things like that have values, so they definitely exist.

LH: Would you mind talking about the vertical we did back in January this year? Like you mentioned, what were some of the moments that made you start to see yourself in a more humbling way? Did any of those moments feel as if you were dancing in shackles?

HH: “Dancing in shackles” has been my sentiment of the past year. The verticals are so different from what you learn in film school, from even your own values. I still don’t necessarily agree with that, but I can respect it, while looking for other ways to earn money.

LH: For that time, you were in the position of the director, and you were in charge of creativity and putting yourself out there in a place that has so many restrictions. You had less room to remove yourself from the set or anything.

HH: Being in a director’s position made me want to do everything perfectly. Fortunately, having Lily there blocked out a lot of the noise.🩷 Interestingly, shooting ReelShort gave me a chance to be bolder: I wasn’t overthinking because it neither represents who I am nor makes me less elegant. And in order to take more dramatic approaches, I channeled those romance dramas I saw on TV when I was little. I kind of felt like a train that was simply going, going forward, and it was kind of fun. But I did make sure that my actors could believe in me.

AP: What do you think about the MFA program? Did it really help you make films or did it only teach you theoretical things? Do you feel that its mode of operating, such as the critique method, were helpful or felt more like false altruism?

HH: MFA was quite meaningful to me, since it was the first time I got to know and work with people from other countries. One of the biggest shocks to me was how eclectic the themes my classmates wrote were. Back where I grew up, there tends to be more of a “box” around what people feel they can write. People had no hesitation writing about things like vampires here.

AP: Was that in any way similar to making ReelShort, like people were just trying things out?

HH: Kind of, since people really brought a lot of things from different cultures, which I wasn’t able to see back in Taiwan. Although sometimes I had doubts about the critique methods, they weren’t as bad as what I was told by people from the industry before. When I shot my thesis in Taiwan, my producer was asking for suggestions on his work, but after actually getting them from people, he got upset. And only after seeing him getting upset did I realize what I’d learned all along: how to take criticism from people. If you are a creator, you will hear all kinds of voices. It felt like growing up to me too, like a necessary part of the process.

AP: How do you review criticism from your colleagues who have completely different styles than yours?

HH: I’ve struggled quite a bit on this, since I internalize a lot. Maybe they have a point, I used to think, but only got myself into a mess later. I didn’t know what I was doing, what I was editing for my film. It was when I couldn’t move forward that I started to ponder things such as, is that suggestion good for me?

Before coming to Columbia, a college professor brought me into a production company owned by Lee Lieh, a renowned actor and producer in Taiwan. She wanted to pool in a lot of young screenwriters and buy their ideas and wasn’t very delicate with her words if your ideas weren’t good enough. She didn’t care about who you were. I had questions about the people she was promoting too. It really scared me and hurt me.

People from the MFA program weren’t as harsh. The industry is intense, terribly. Even though people in my year weren’t very close with one another, I made some good friends, mostly international students, and we helped one another greatly, confiding in one another. My best friend, Álvaro, is optimistic and practical. I often turned to him when I had troubles. He would always help me analyze the problem, instead of just comforting me or neglecting me. I depended on him quite a lot. 🩷

HZ: Let’s talk about the future! Any ideas for your next project?

HH: I’m working on a story about a sister teaching her younger brother how to ride a bicycle. They keep encountering funerals, all day since the morning, passing by funeral troops, all the way to the river bank. The sister gets a call about their mother who was dying. On the other side of the river bank, they see burning of the deceased’s clothes. I always like river banks, not sure why, just things that look bleak. This is the gist of the story, sad and emotional. I’m also experimenting with a looser story structure.

AP: What do you do when you’re not making films?

HH: Hmmm…what do I like to do in my free time? 🤔I like watching vlogs, something that’s close to life. There’s this family I follow on social media; their vlogs show how they turn the negative things in life into happier situations. You can see their kid grow up too. It’s almost as if they keep you company, though you don’t really know them.

AP: I know a lot of people, including myself, can’t relax by doing something that is somewhat close to their field. For instance, I used to have a hard time relaxing by reading books, because I’d get into work mode. Would you feel this way watching those vlogs?

HH: The vlogs don’t really make me feel this way, because they have nothing to do with my real life. If I were to watch a movie today, I’d feel differently.

AP & HZ: That’s all!

HH: Thank you! You are all so cute :))

You can find more of Hsiaowen’s work here and on Instagram @hsiaowenhsu.